Exercise 1 - Deep Squats

Alex Rabindranath

March, 2013

Deep Squats

The deep squat is a great exercise that incorporates all of the major leg muscles and is beneficial in both rehab and sport specific exercise regiments. Ankle dorsi flexors and plantar flexors, knee extensors and flexors, and hip extensors and flexors are all engaged at different stages of the deep squat (Robertson et al., 2008). The involvement of all the lower extremity musculature and joints makes the deep squat a perfect exercise to train or restore functional movements in the legs. Deep squats have been shown to increase dynamic speed-strength and dynamic maximal strength (Hartman et al., 2012), as well as improvements in high velocity movements, which are integral to activities that involve running and jumping (Drinkwater, Moore & Bird, 2012).

Deep squats can also be modified to focus on strengthening specific muscles, making it an ideal exercise for many training and rehab programs. Bryanton et al. (2012) have showed that the hip extensor, knee extensor and ankle plantar flexor musculature can all be specifically engaged, and can therefore be specifically trained, by modifying squat load and depth. Knee extensors are activated more by increasing squat depth, the ankle plantar flexors are engaged most at heavier weight loads, and the hip extensors are stimulated most by increasing both squat depth and load (Bryanton et al., 2012). These variations in muscle activity can help practitioners and trainers make rehab or sport specific modifications to the deep squat exercise in order to isolate muscles and maximize efficacy of training.

When compared to partial range of motion squats, the deep squat is much better for general strength training due to its functional aspects (Hartman et al., 2012). Training regiments and recreational weight training programs have often used partial range of motion squats with heavy loads in order to achieve their desired results, but these methods have been proven inferior in many aspects (Hartman et al., 2012, Drinkwater, Moore & Bird, 2012).

Only at the ranges of motion and joint positions achieved in deep squats are the neural and morphological requirements met to stimulate positive acceleration from hip and knee extensors (Hartman et al., 2012). Sets of partial range of motion squats were deemed to be useless in comparison to full range of motion squats because of their inferiority in maximizing force, velocity, work, and power (Drinkwater, Moore & Bird, 2012). From an injury prevention perspective, deep squats have a lower risk of injury compared to partial range of motion squats, due to the deeper joint positions achieved when performed properly and the lower weights being used (Hartman et al., 2012). The ability to achieve greater velocities and speed-strength performance while using lower weights results in a lower risk of injury because there are less tensile forces created at the knee and less compressive and shearing forces created at the thoracic spine (Hartman et al., 2012).

Clearly deep squats are the superior choice in comparison to partial range of motion squats. The benefits of engaging all the lower extremity musculature, creating sport-specific increases in strength and velocity, increasing functional movements, and being modifiable to isolate certain muscles make deep squats a highly transferable and valuable exercise. Whether being used with high-level athletes, rehab patients, or recreational exercisers, the deep squat is an exercise that can be tailored to meet many training goals.

Deep Squat Proper Form

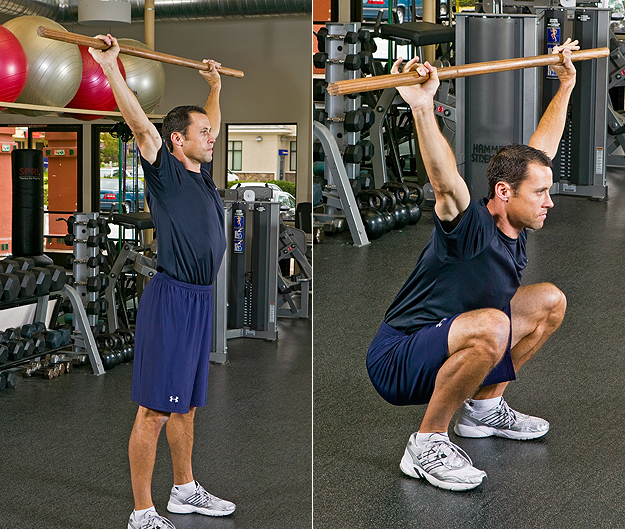

Figure 1

The deep squat takes the same form as any squat, but entails the hips dipping below parallel to the knees and even as low as the ground. The inside of your feet should be shoulder width apart throughout and your arms should be above your head, keeping your mid-arm in line with your ears. Holding a dowel, stick or other long straight object (golf club, hockey stick etc) is helpful to keep proper form. Make sure your knees are positioned approximately above your baby toes and that they do not go out in front your toes during the exercise. Ensure that your knees stay out (lateral) above your baby toes and do not let them move inward (medial) during the squatting motion. Maintain a good arch in your feet while having your weight focused on your heels, and specifically the outside of the heels.

Figure 2

Start the deep squat in an athletic position and then make a sitting back motion as opposed to a sitting down motion. Squat down until your thighs are just below parallel but continue further down if you can (Figure 1). Keep a neutral lumbar arch when squatting down and keep your hands above your head. When pushing up to stand back up from the deep squat make sure to keep all the proper aspects of form mentioned above and push into the ground through your heels.

References

Bryanton, M.A., Kennedy, M.D., Carey, J.P. & Chiu, L.Z.F. (2012) Effect of squat depth and barbell load on relative muscular effort in squatting. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(10), 2820–2828.

Drinkwater, E.J., Moore, N.R. & Bird, S.P. (2012). Effects of changing from full range of motion to partial range of motion on squat kinetics. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(4), 890-896.

Hartmann, H., Wirth, K., Klusemann, M., Dalic, J., Matuschek, C., & Schmidtbleicher, D. (2012) Influence of squatting depth on jumping performance. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 26(12), 3243– 3261.

Robertson, D.G.E., Wilson, J.M.J. & St. Peirre, T.A. (2008). Lower extremity muscle function during full squats. Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 24, 333-339.

Saez Saez De Villarreal, E., Izquierdo, M. & Gonzalez-Badillo, J.J. (2011). Enhancing jump power after combined vs. maximal power, heavy-resistance, and plyometric training alone. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(12), 3274-3281.